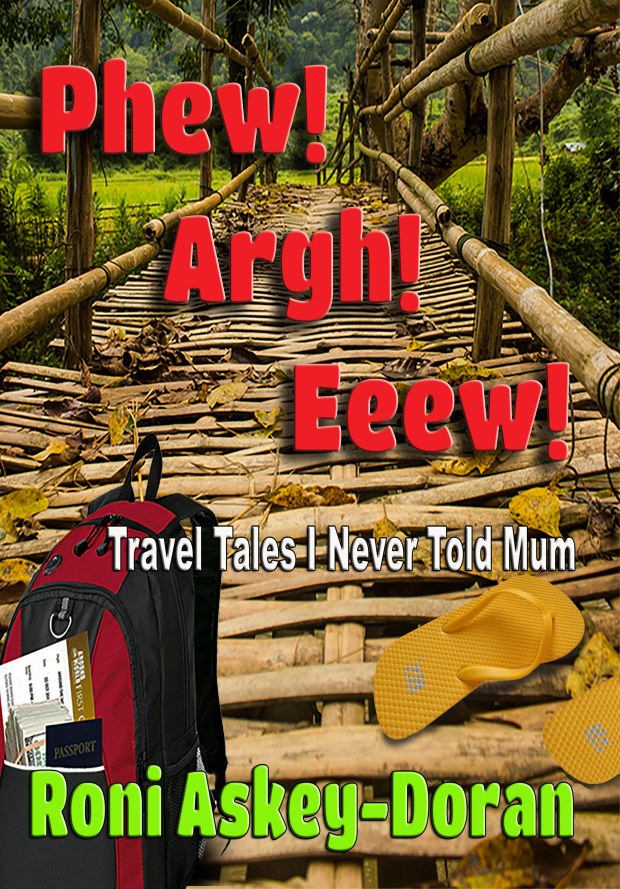

Phew! Argh! Eeew! Travel Tales I Never Told Mum is a fantastic collection of short travel tales so enthralling, so gripping, and so chilling to read that you’ll never leave home again.

When this intrepid young backpacker first embarked on her adventures around the globe, even her own wild imagination could not have conjured up some of the unforetold events that took place in her thirty-five years of travel.

Despite being hijacked in Bulgaria, nearly dying of Malaria in India, being imprisoned in Ecuador and almost blown to pieces in Turkey, Roni lived to tell her stories in the vivid and humorous style for which she is known. The only person she never told was her mother….

In the safety of your armchair, hang on for dear life as Roni takes you on a journey you will not soon forget.

Visit the Bookshop to purchase a copy

Stop by Books by Roni on Facebook and LIKE!

To share this link: http://wp.me/p4GYVW-14

Read one of the fantastic short stories from Phew! Argh! Eeew! here:

Syria

Taken Hostage

Determined to get an early start, I was on the road at the crack of dawn, hitchhiking out of Homs, Syria’s third largest city. The destination of the day was the impressive Krak des Chevaliers (Qala’at al-Hosn), set majestically atop a hill just north of the Lebanese border. An isolated Medieval fortress in the middle of nowhere, it was just the kind of place I like to visit.

As the sun rose over the horizon, I stuck out my thumb on the highway, and waited for a ride. In the nineties, I used to be able to claim that I had never been in a country where I hadn’t hitchhiked. It wasn’t about the bus fare, it was the feeling I got on the side of the road while thumbing down a vehicle. Many cars passed without a glance in my direction. That was okay with me. The right car, and the right driver usually came along at exactly the right time. It was about the adventure of traveling, the journey, and the people I met along the way. Hitchhiking was one of the best ways to meet local people. So there I was, on the verge of a highway, bumming a lift.

“Where you go?” asked a policeman in a dark uniform as he pulled up.

“Krak des Chevaliers.”

“I go Snoon. You come.”

Limited English was never an obstacle. I climbed into the police car and we headed down the road towards Snoon. Over the next twenty-five minutes, I learned that Karam was going home to his family after a long night shift in the city. He had four children, one of whom had just started high school. He was worried for her future. She wanted to study Fine Arts in Damascus and he didn’t know if he would be able to afford the

university fees. The other issue was his wife.

“She want Amira marry,” he said wistfully. “Not go school.”

“Amira can do both,” I said, sure his daughter would be fine.

At the turnoff to Snoon, Karam dropped me off, but not before flagging down a private charter bus and instructing the chauffeur to give me a ride to Talkalakh. The driver could hardly defy a man in a police uniform. The bus was going to Tartus.

“Talkalakh. Turn there,” Karam told me.

The turnoff was just past Talkalakh. The road to the castle traveled a wiggly route around the edge of the Gap of Homs. There was a longer way around on Highway 43 that would have been a lot more scenic, but I wanted to be in Tartus, on the Mediterranean coast by evening.

Sensitive to Middle Eastern culture, I was dressed in long pants and a long-sleeve shirt. There was a headscarf in my pack that I usually used when I visited mosques. Though exposed, my hair was tied back neatly for the journey. Twenty nine pairs of smoldering black eyes pierced the back of my skull for twenty-five minutes as I sat on the floor at the top of the steps for the ride to the turnoff. Not a soul on the bus spoke a single word of English.

Sadly, it was impossible to strike up a conversation with men who stared silently, their faces stone masks of intensity. It was impossible to tell if it was their disbelief at a female hitchhiker, their disapproval of a woman not wearing a headscarf, or resentment that they were forced to pick me up. For twenty-five long minutes, the tension was so tangible it could have been strummed. I sat like a statue with my eyes focused intently on the road that ran alongside Lebanon’s northern frontier. Relieved to be off the bus, I smiled and waved as it rumbled away. One man in the back grinned and waved out the window as the bus disappeared.

In the hot sun, I waited at the turnoff. From my backpack, I took a sarong to wrap around my head and shoulders as shade, the novel I was reading, and the bag of food I packed in Homs the night before. I also carried plenty of drinking water in case I

got stuck anywhere for too long. Unpacking the falafel I bought from a street vendor the previous night, I sat on my tightly stuffed backpack and tucked in to the thick pita bread damp with garlic yogurt and chili sauces. There was no traffic in any direction.

A while later, as I popped sweet fresh dates and juicy ripe figs into my mouth, I wondered if I was on the right road. Had there been some miscommunication between Karam and the bus driver? There weren’t any other roads to turn off onto. I had to convince myself I was going in the right direction, in the middle of a country I knew little about. I didn’t speak more than five words of the language, was no longer in possession of the map I bought in Damascus, and was traveling alone and by the seat of my pants. An hour passed before a rusting red tip-truck pulled up.

“Qala’at al-Hosn?” asked the driver.

Fortunately, I’d heard the Arabic word for Krak des Chevaliers enough times to recognize it.

“Naam,” I replied, nodding assent and smiling, adding “Shukran,” to express my thanks.

I climbed up into the cab and sat beside his wife and two children. These generous people also didn’t speak a word of English, but that was no obstacle for the two little boys.

“Esmi Roni,” I introduced myself.

“Esmi Hadad! Esmi Mahdi!” shouted the boys.

Hadad and Mahdi played hide and seek with me, hiding behind our hands, and yelling “BOO!” whenever we revealed our faces. The little boys squealed with delight and the three of us laughed and played for the twenty minute journey. The boy’s mother smiled and patted my back as I descended the cab at the base of the castle.

“El Hamdul Allah,” intoned the driver as I got down, reciting a simple prayer.

“Shukran, shukran, shukran,” I replied, my hands clasped at my chest and my head bowed.

The whole family waved out the window, calling out in Arabic and laughing raucously as the truck rolled down the dusty road.

A World Heritage Site, Krak des Chevaliers (Knight’s Fortress) was once described by British archaeologist, Thomas Edward Lawrence, as the best preserved castle in the world. Never before had it been so effortless to travel back in time, and land

squarely in the eleventh century.

While the Hellenistic city of Akko was nominated to serve as the military headquarters of the Crusaders in the Holy Land, the Krak des Chevaliers became their most formidable bastion. This tremendous fortress, the largest Medieval castle in the Middle East, was first built by the Kurds and later rebuilt by the Crusaders, survived the Middle Ages in remarkably good condition. The castle preserves some of Christianity’s most important artwork, artifacts, and relics from the crusader period that can be found in the Middle East.

The Kurdish Emir of Homs built the first fortification at this site in 1031. It was called Hisn al-Akrad (Castle of the Kurds) and housed a garrison of Kurdish soldiers. The original castle was much smaller, consisting of a single enclosure, the walls of which correspond with the present inner ward. During the First Crusade in 1099 it was captured by Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse (a.k.a. Raymond de St. Gilles). The Count abandoned the castle after only ten days of occupation, leaving to march on Jerusalem. It was retaken by Tancred, Prince of Galilee the following year.

In 1142 it was gifted to Raymond II, Count of Tripoli, and then handed over to the Knights Hospitaller who redesigned and fortified the castle to create a starting point from which

to launch fresh campaigns. Renovations included a bakery, a refectory, warehouses, latrines, two large halls and a chapel in the French Gothic Style which later became a mosque. During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the fortress was damaged by a series of earthquakes and subsequently repaired, becoming increasingly stronger with each reconstruction.

Mameluke Sultan Baibars conducted a month-long siege on Krak des Chevaliers in 1271, and negotiated an honorable surrender from its occupants. The Knights were granted safe passage to Tripoli. Baibars restored the walls and added two towers to its south-western side.

In 1285, Sultan Al Mansur Qalawun built the square tower in the outer southern wall.

Krak des Chevaliers Castle was used until it was abandoned at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Decades later, the locals built a small village inside the castle. It was bought by France in 1927, and they removed the village and restored the castle before donating it to Syria in 1947.

First through the gate in the morning, I had the whole castle to myself for several hours. It was easy to by blown away by Krak des Chevaliers; gusty winds howling over the hill were strong enough to make walking around the historic site a battle in itself. Donning a sweater to visit the ramparts, I was careful not to be swept across the plains on the powerful breeze.

Enthralled, I explored the castle from top to bottom, inspecting limestone brickworks, admiring the lintels, and venturing into halls and rooms which had once been vibrant with life. I could picture the Knights slurping hot soup from wooden bowls at a long table in the dining room. In the dark dungeons, I could almost hear the wails of the prisoners. Fending off hunger for as long as I could by munching on dates and figs as I thirstily drank in the history of the magnificent castle, I stretched out my visit for as long as possible. Just after noon, when a busload of gabbling tourists arrived at the main gate, it was time to leave.

Once again, I sat at the roadside and waited for a ride back to the turnoff. My position just south of the main gate offered little shade. Fortunately, I wasn’t there long. A friendly man in a delivery van gave me a ride on his way back to Homs. Uncertain it was okay to leave me in the middle of nowhere, he nervously waved goodbye as he left me alone on the ride of the road. His fear was unfounded. I sat on my pack and read to pass the time.

A few days on the coast at the four thousand year old city of Tartus was next on my to-do list. Originally, it was founded as a Phoenician colony of Aradus. There is something about ancient remains that gives me a good perspective of my place in the world. I have been alive less than half a percent of the time Tartus has been in existence.

Peppered with remnants of the Crusader invasion, the second largest port city in Syria promised a combination of relaxing beach time and rich history lessons. I just had to get there; it was fifty-five kilometers. Less than half an hour passed when a white minivan pulled up.

“Where are you going?” asked a young man with good English.

“Tartus,” I said, wondering if they could take me that far.

He leaned back and discussed this with the other passengers for a moment. Then, the side door slid open and several hands waved me inside.

“We’re going to Tartus,” said the young man. “We’ll take you.”

“Thank you. I appreciate it.”

We made introductions, and they established I was the first person from Tasmania they had ever met. Fascinated, they asked endless questions. Several of the group of three men and three women spoke English and translated to the front passenger who didn’t. It wasn’t long before I learned they were members of one family. They lived in Tartus and had been visiting older family members in Homs for a few days. They permitted me to join them for their journey home.

“Are you hungry?” asked one of the sisters.

“Yes, a little,” I confessed, having consumed all my food.

“We’re going to stop for lunch. It’s a famous place for barbecues,” said the friendly young man.

“We always stop here on our way home from Homs,” added the eldest sister, giggling.

The van turned off the main highway towards Al-Hamidiyah and bumped over a rough road for fifteen minutes. Arid terrain stretched out in all directions. Western Syria isn’t green. When we arrived at the car park, everyone got out and stretched, some loudly yawning before leaning down to touch their toes.

“It’s not a long drive, but we didn’t get much sleep last night,” explained the oldest brother.

A massive tent-structure made from what appeared to be a recycled Big Top with cement foundations and ornate gates covered in vines loomed above as we entered the cavernous restaurant. Thirty tables were set out in straight lines, each able to seat a party of ten or twelve. The place was buzzing. Waiters ran to and fro, taking orders for food and drinks, and delivering large trays of steaming meat, massive bowls of vegetables and salads, tureens of soup and mountains of bread in woven baskets.

A smartly uniformed maître d’ rushed to greet us, shaking hands and chatting pleasantly with the mustachioed van driver who turned out to be everyone’s father. Adnan and his wife, Maya followed the man into the dining area, followed by their daughters Qamar and Zeinah, and their sons Fathi and Sayid. I trailed behind, curious and excited about what was to come.

As we approached the long table draped in a white linen cloth, several waiters appeared from nowhere and simultaneously pulled out the carved wooden chairs with a flourish. The scene was so surreal, I felt a bit like I had come face to face with the story of Aladdin, his magic lamp and its famous Genie. My wish of a decent meal was about to be granted.

“What would you like to eat?” asked Fathi.

“Is there a bathroom? I want to wash my hands,” I said, secretly thinking about washing my face, my neck, and my arms, legs, body and even my hair after a morning in the dusty Syrian west. A change of clothes wouldn’t have gone astray either.

Before I could blink, a smiling waiter appeared at my side to guide me to the facilities. Being dressed in rags and treated like royalty felt rather ironic. Chuckling to myself, I stepped into the bathroom. Gleaming white marble adorned with shiny gold fittings surrounded my pauper’s body. There was, in fact, a shower in the last stall. It was tempting. Choosing to behave myself and respect my hosts, I restrained the urge to stand naked under fresh running water, and washed as much grime from my arms and face as I could before returning to the table.

“We have ordered!” announced Zeinah as I took my seat.

“Wonderful! I’m hungry,” I replied smiling.

A waiter placed four large pitchers of iced water on the table, and set a crystal glass in front of each place. Satisfied we could quench our thirst, he picked up the empty tray and ran back to the kitchen. Sayid immediately took charge and poured drinks for everyone.

Between Arabic whispers and English statements, the conversation flowed back and forth. It turned out that the four siblings had studied at a language school in London. Over the course of his career as an import/export consultant, Adnan had done business there and had friends with whom he could entrust his offspring for a few months. Most of them spoke well, fluently as opposed to accurately. In order of oldest to youngest, they were Fathi, Qamar, Sayid, and Zeinah. Maya understood our banter, but was terrified to speak in case she made a mistake.

Heaped platters of food were brought to the table. From a large family of seven, and accustomed to preparing meals, I couldn’t even imagine how seven adults would be able eat everything placed in front of us. There would be leftovers for a week.

“You must try this!” Qamar slid a slice of meat from her fork onto my plate.

The flavor was familiar and unusual at the same time. I liked it. A roar of approval went up at the table. I had just eaten my first piece of roasted goat. In turn, each member of the family put a morsel on my plate and suggested I try it. From Jeweled Rice to stuffed vine leaves and eggplant fatteh, I sampled the best of Syria’s cuisine. Tasty kebab karaz made from lamb meatballs, and kubbah hāmda made with bulgur and pomegranate sauce passed my lips as I dined like royalty with the wonderful family from Tartus.

As we ate, a singer performed on the stage, twirling and whirling in glittering full skirts as she belted out traditional folk songs with her incredible voice. After a dozen songs, she took a break. A few minutes later a belly dancer appeared, shaking her agile hips to the drum beat in ways most western women can only imagine. Soon after the dance, an ensemble of five men entered the stage holding traditional instruments; Oud (lute), Kamenjah (spike fiddle), Qanoon (box zither), Darabukkah (goblet drum), and Daf (tamborine), which they played and sang as a choir. The entertainment went on for over an hour before muted piped music filtered through the air in the restaurant once again.

“Do you know where you will stay in Tartus?” asked Adnan, passing over yet another piece of Mahshi; zucchini stuffed with ground beef, rice and nuts.

“No. I haven’t figured that out yet,” I admitted, digging in to the delicious food.

Hotels weren’t usually planned as I went. It was easy enough to turn up in town and find lodgings. Unless there was some kind of important cultural event taking place at my destination, accommodation wasn’t something I ever stressed about; there was always a place to stay.

“Have some Baklava,” suggested Sayid, passing the laden tray.

When offered hospitality in the Middle East, I had learned to accept with a smile. To refuse can be considered offensive. I had also learned to leave food on my plate to indicate I had eaten enough. To empty the plate was akin to a request for more food. Even though baklava was too sweet for my taste, I took one small piece from the tray and put it on my plate. Eating it was an art form in itself which required approximately one liter of water as an accompaniment; just to wash down the sugar.

“We, you, hostage,” announced Maya, speaking her first English words all day.

I almost spat my mouthful of water onto the table. “What?”

“Hostage,” she repeated, pointing at her chest and then at me.

“I, you, hostage.”

How does one refuse such an offer? I wondered. Well, that’s such a lovely offer, but I don’t really think it will fit into my plans, I was tempted to say.

Saving us all from a terrible fate, Fathi intervened.

“Mama?” he asked, reverting to Arabic to figure out what she was trying to communicate.

After a short exchange, the siblings burst into giggles all at once. At this point, I wasn’t certain whether there was cause to be alarmed. My usually sharp instincts didn’t predict danger.

“Host!” giggled Sayid. “She wants to say host.”

“Excuse Mama, she is confused with the words,” added Qamar, trying to stop laughing.

“She means to say that she would like to host you,” explained Zeinah.

“Sorry,” said Maya, blushing fiercely after her children had explained what she said.

“You must stay with us! Do you agree?” said Zeinah, clapping her hands.

“Yes, you must,” agreed Adnan. “You can be our guest for as long as you wish.”

How could I refuse?

Thus, I agreed to be taken hostage by a wonderfully generous and friendly Syrian family from Tartus.

~0~

PSSST…. Wanna buy another short story like this one? For just $1 per month you can support the author and get to read an exciting short travel story from Roni’s work-in-progress “OMFG! Travel Tales I’m Never Telling Mum” every month!

Find out more on Patreon/booksbyroni.

Cheaper than a cup of coffee, and more exciting than your commute to work, a great story every month will help you escape for a few moments!

If you liked this short story, there are 34 more fantastic travel stories in “Phew! Argh! Eeew! Travel Tales I Never Told Mum” available for purchase from Smashwords and Amazon (see the link to the bookshop above).

Support the Author Here

~0~

Book Reviews for Phew! Argh! Eeew!

Kiwiscantfly on 22 Oct 2017

Five stars

“Thoroughly enjoyable book. Not only does it transport you to the regions that many of us will never venture describing them beautifully, but regales with many a tale of adventures, some wonderful, others frightening.”

Ros on 26 Dec 2017

Four stars

“Roni tells the travelling tales the rest of us can never tell our mums! What doesn’t kill you makes for a good story.”

mark masserant on 27 Jul 2018

Five stars

Format: Paperback

Another great read by Roni! I think you’ll love it. Exciting and humorous in a way only Roni can do it. Check it out!